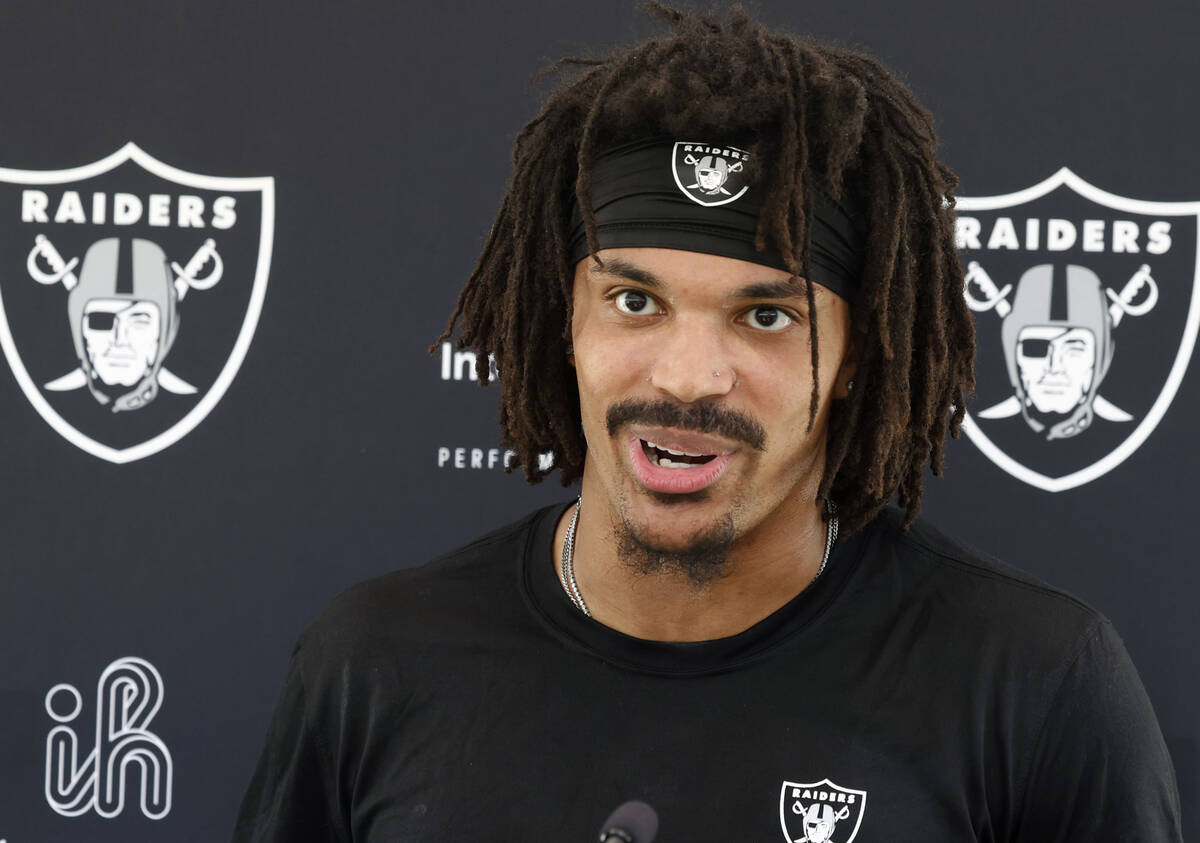

Pro Football Focus grades can be a polarizing topic among fans and NFL players and executives alike.

The sports analytics company’s accuracy and relevance tend to be lauded by those who score well and demonized by those who don’t in general.

But what really goes into the process?

PFF director of content Austin Gayle spoke to the Review-Journal’s Heidi Fang on a recent episode of the Vegas Nation Takeaways podcast and peeled back the curtain on how those numbers are created.

Gayle also provided insight into what positions he and his colleagues are most confident in rating and where the system can be improved.

This is an excerpt from the podcast. It has been edited for clarity.

Heidi Fang: PFF has always mystified me in terms of numbers. What was the basis of how it started with grading and rating players?

Austin Gayle: It all starts from our founder, Neil Hornsby, who’s from the U.K. He was a big American football fan and felt that there wasn’t enough data available to the average fan, or even to teams, that better evaluates players and that was more predictive. Twenty years ago, we weren’t talking about missed tackles, drops, pressures, pressure rate.

In addition to that, you want to grade every player on every play from a scale of negative 2 to positive 2 at 0.05 increments. And from there, normalize that to a zero to 100 scale for ease of understanding so people could see 90 versus 80 rather than +12.5 versus -1.5. That’s led to a lot of success working with NFL teams, working with college football teams, and providing that same data so they can evaluate players better and make trades better but also provide that same data to consumers.

People who play fantasy football, people who bet on games want more predictive data beyond touchdowns and yards per carry. So PFF continues to evolve. So much of what we’re going to do is collect, analyze and leverage data that we feel is more predictive in predicting future player performance, future team performance.

HF: When it comes to looking at things, like for guys who aren’t necessarily throwing every pass or catching every ball, how do you arrive at the numbers for an offensive lineman, for instance?

AG: For offensive tackles, it’s split up. Obviously run blocking, screen blocking and then pass protecting. With run blocking, it’s three analysts who are looking at every single player on every single play and creating a baseline expectation for what that tackle is supposed to do on that play. If he’s the backside of a zone, it’s cutting off a guy or whatever it may be, you’re grading him from negative to positive 2, zero being his expectation. If he just hits expectation, it’s zero. If he decleats a guy, it’s a plus 1. If he misses a block and falls down, it was maybe a minus 0.05. And you’re doing that for every run-blocking play. For pass protection, you’re getting a zero if you don’t allow pressure. You’re getting a 0.05 if you pick up an extra guy off a stunt. Or you’re getting a minus 1 if you get beat right off the snap and give up a pressure, even if the quarterback isn’t sacked.

So for offensive linemen, our grading is really predictive because you’re grading so many more events. Every single play, you’re either winning or you’re losing. Did you block the guy or did you not?

Where our grading still needs to improve more is off-ball. A safety that maybe doesn’t make more than two tackles in a game. How are you grading them effectively? Offensive linemen, defensive linemen, quarterbacks, those players get graded so consistently and are in these binary matchups of winning and losing so consistently, those grades are actually really predictive and some of our best.

HF: So let’s take the decleats. If it’s plus 1, plus 1, how do you get all of the data to arrive at the one number that will go into the system?

AG: All the data is inputted into a back-end software that we’ve built and is run through three people.

The first person looks at the film, the second looks at the film, the third looks at the film and then you have someone reviewing those three uses and identifying the mismatches. From there, it’s put through an algorithm that puts the grading on a normal distribution. So the best player in the NFL is a plus 20 in a game, and the worst player is minus 15.

You’re distributing that across the normal bell curve, so that way you can put it on a zero to 100 and say 90.5 versus an 80.4. That’s also like the algorithm is to figure out where you line up. It’s easier to create pressure as an edge defender than it is for a defensive tackle, because you’re playing more in a phone booth. How often should you create pressure?

It’s important to call out that PFF’s grading system is very much production grades. Obviously they’re more predictive than passer rating or yards per carry or receptions, but it’s still a descriptive stat.

If the player earns a 90.6 grade on the season, that doesn’t mean he’s a great player. That just means that season he graded really well. It’s similar to if a quarterback throws for 6,000 yards in a season. Does that mean he’s a great player? No. He just threw for 6,000 yards. Is that indicative of maybe him having more future success? Yes, but it’s not necessarily an end all, be all.

Sometimes PFF grades can be viewed that way. Sometimes grades are like, ‘Oh, (Rams cornerback) Jalen Ramsey got an 81.1 in that game. Does he suck?’ No. It’s more speaking to his production.

HF: How did you determine what categories would be the most important for grading each position?

AG: What I look for specifically in college draft evaluation is identifying stats that are more predictive going from college to the NFL. A lot of those stats are arm length, 10-yard split, stuff that we’ve been looking at for a long time evaluating players.

HF: Let’s take Cooper Kupp. Is the same person going through and giving the analysis to add to his numbers throughout the season, or is it spread out among the staff?

AG: Definitely spread out among the staff. We don’t like to have the same human beings grading the same teams. We want to remove people of bias.

It’s a triple blind process where the first person doesn’t get to see what the second person says about the grades. The second person doesn’t get to see what the third person says about grades. That way there is some form of objectivity, because bias could creep into the data if you have a Bucs fan grading the Bucs.

But it’s definitely not the case, because we have so many different people doing it. Even a fourth person in the quality control group looking things over and seeing how people differ. It’s definitely something that’s been an ongoing, improving process.

Contact Heidi Fang at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @HeidiFang.